In partnership with Cooperative City magazine on collaborative urban practices, we had a public webinar on 24th April 2020 focusing on how urban commons are an opportunity to ensure social cohesion in the face of the upcoming economic and social crisis. Urban Commons are all those spaces, services and resources that are directly managed by local communities for their wellbeing. Taking care of such common goods isn’t only beneficial for the immediate needs of the citizens – in fact, urban commons can play a crucial role in building a more cohesive – and inclusive – society.

Building solidarity is a must, especially during such a challenging time. GeCo (Generative Commons) Living Lab is a project that maps solidarity initiatives throughout Europe with the aim of creating an infrastructure to facilitate the sharing and networking process. During this period we have been thinking about solidarity in the crisis, meeting many municipalities, associations and informal groups who normally react towards the everyday crises, and thought about asking what kind of activities they are carrying out in the current situation.

We know that cooperation and solidarity need physical contact and it’s not easy to think about a collective reaction in such a period. Yet, we organized this event to share responses to common social needs.

Hosting the panel discussion: Alessandra Quarta, Associate Professor at the University of Turin and Project Coordinator of GeCo, and Daniela Patti, co-director of Eutropian.

Guests:

Ugo Mattei – Academic Coordinator at IUC (International University College of Turin) – Turin, Italy

Duygu Toprak – editor of Ortaklaşa book on commons in Turkey – Ankara, Turkey

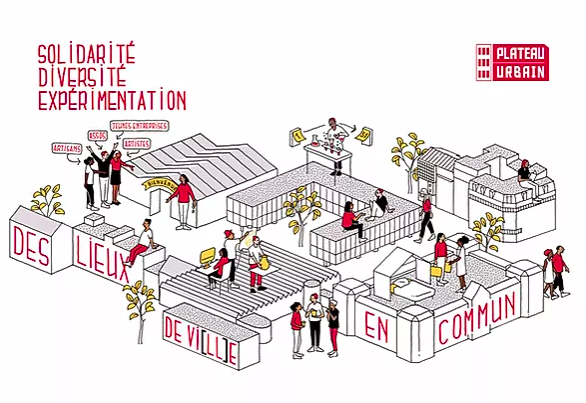

Martin Locret – Project Manager at Plateau Urbain, a cooperative supporting temporary use of empty buildings – Paris, France

Joacquin de Santos – European Projects Manager at Community Land Trust Brussels – Belgium

Andrea Simone – co-founder of Nonna Roma, mutual aid association operating in Pigneto district, Rome, Italy

Natasha Dourida – co-founder at Communitism, a community of creative professionals running a community space promoting mutualistic practices – Athens, Greece

Key Learning Points for this episode were multiple, some of the highlights were:

- Commons, in their broadest interpretation of solidarity and sharing community based practices, are proving to be essential in providing essential welfare services to the marginalised members of our communities;

- Even in “normal” times, commons need space to provide their services and support to marginalised communities, such as schools, education or leisure, but this is especially true under the current circumstances, in order to organise food distribution and many other activities.

- We need to ensure recognition through political and financial support to common spaces, to ensure these will survive even after the emergency, as a long term community support.

Urban Commons are very linked to a physical perception. Right now their political activities are developing in different ways, for example, they are shifting towards the digital space.

How can commoning profit from the current situation?

Ugo Mattei – The COVID-19 outbreak is just another dramatic capitalist crisis. Of course, those who suffer the most are the ones who find themselves at the “bottom of the pyramid”, affecting society at both macro and micro levels. On the micro level, many spontaneous commons are developing during this crisis – for example, an ever growing spontaneous common can be a basket full of food donations at the baker’s, ready to help those who can’t afford food. At macro level, capitalism jumps from crisis to crisis, there is nothing new about it, but this is a huge opportunity we wouldn’t find in any other moment, because many things can happen during a crisis, while they can’t happen during a normal period of mass production. Of course, change by itself doesn’t mean it’s positive. When the crisis hit in 2008 there was nothing that could be offered as an alternative, we weren’t prepared. The commons movement was not organized – it actually started later, as a reaction to that crisis, all over the world. Thanks to our previous experiences, we now have the chance to use the digital space to make the idea of commoning become hegemonic and finally act on inequality transnationally.

Many urban commons are specifically thought to revitalise urban voids, such as abandoned buildings. How are they reacting towards social space when it cannot be physical anymore, and what about those people who don’t have a home they can stay at?

Martin Locret – Our activities are usually aimed towards independent cultural workers, and we run them in empty and / or abandoned buildings that we wanted to put to good use. We were able to immediately say yes because we always kept in mind the fact that urban commons should be able to respond and adapt as quickly as possible. We are not doing this on our own – we have strong ties with Aurore and Yes We Camp, organisations that work in the social and urban sectors that allowed us to be compliant with the hygiene protocol and provide our physical spaces with all they needed to serve homeless people, turning them into daytime shelters. We provide the homeless with food, telephone, internet and, of course, hygiene facilities. We also managed to organise a space where they can rest for a few hours if they need to.

Joaquin De Santos – We usually involve our residents in a community building process even before they move in. This contributed to the creation of an overall sense of cohesion, resilience and solidarity that we are witnessing in this moment. We are also trying to build a community around our members: we are always available and help them know their rights and the benefits they are eligible for. Many of them are not acquainted with the current regulations and don’t know how to access support, while those who are on the waiting list for a home can ask us for legal assistance in case they have problems with their current landlords due to lack of income. The current situation convinces me even more of the fact that projects that are based on solidarity and mutual help and cooperation really make a difference and build stronger, more resilient communities.

Natasha Dourida – Luckily, we don’t have an emergency in terms of sustaining the building we are housed in, as we were granted the venue free of charge in exchange for renovations on our side. Homeless people are living there at the moment, so at the same time we are helping them out and they help us renovate. We are a relatively new project as we started in 2016, and grew very rapidly. We set up a clothing donation space, we run a gallery, a cinema and we organise other cultural events, but due to the pandemic we are obviously not operating. This pandemic caught us in a period of stillness, as we were all redefining our objectives. Each one of us is active in several other initiatives, so we will most probably have the chance to share our insight and contribute to other commoning activities.

Provision of food is becoming an issue for an ever growing number of people. What changed during this crisis?

Andrea Simone – Nonna Roma was founded in 2017 in the Roman district of Pigneto.

We immediately realised how many people were living in poverty and very close to starvation despite the heavy gentrification process. Before the Coronavirus outbreak our activities included free legal assistance, educational activities and an entrepreneurship program for bottom-up, grassroots initiatives, in addition to a food aid programme that served around 300 families. We are now delivering food at home to more than 2000 families. Teachers, workers, and many “new poor” are now showing up. Luckily, the group of volunteers is now bigger (200+ from just 50) and we are receiving lots of donations. On a darker note, we cannot keep up the rest of the programmes. We shifted to online activities, however downsizing our spectrum of activity. Community building needs short social distance, so right now we are facing huge challenges, hopefully just temporarily.

Martin Locret – We have been contacted by the Municipality of Paris – they asked us if we could help with food distribution, as we run our activities in empty and / or abandoned buildings. We were able to immediately say yes because we always kept in mind the fact that urban commons should be able to respond and adapt as quickly as possible.

Duygu Toprak – In Turkey, every legal solidarity activity is classified as an enterprise as Turkish law doesn’t allow for other legal statuses to operate, so most of these spaces are registered as commercial activities. As a consequence, they are now closed, but apart from urban gardens, those commons that managed to join local food provision programmes can distribute hygiene kits and food packs.

How can we reinvent a new model of commons and societal development for the future?

Ugo Mattei – I am very worried about the future because we are facing a strong restructuring of the fascist model, witnessing increasing surveillance and concentration of capital and power. We need to create a strong and serious network of relationships between people who refuse to be patients, we need to be transparent about what we do, and we need to be very well organized. The commons have to show very openly – and very politically – what they do, and they must go very clearly against the work of most political processes who are already profiting from the situation to take away civil rights from the citizenry. Commons are now the welfare system while governments are failing and political parties are only focused on the next elections. There are some good signs, however. Somehow people are starting to understand that society is made of people that need to be connected.

Natasha Dourida – From a personal point of view, as well as from Communitism’s side, this lockdown paradoxically worked beneficially for our commoning activity. We are taking time to decode what has happened and what is happening, how it is affecting us as individuals and what we want to do next. The current situation made us focus a lot more on how to improve our digital presence, activity and creativity so that we can be ready for the next steps.

Daniela Patti: In many countries, the excuse of the COVID-19 crisis is being used by governments to take even more power. On the other hand, a lot of the commoning activity was born as a way to counteract the actions of governments.

Where do you think that urban commons can help us?

Ugo Mattei – We need to be awake and extremely critical. A very thin line separates being an active citizen from becoming a nationalist serving a police state, so we need to refuse the mental medicalization of society, as that doesn’t allow subjectivity to survive. Italy is already undergoing a huge crisis in terms of freedom of speech, questioning power is becoming ever more difficult, bigotry is rampant. Commoning can help society understand that only by helping each other can we survive the many issues we find in front of us, and that resistance needs to be built from the bottom up, and not the other way around.

Duygu Toprak – I recently published a book on commons in Turkey funded by the European Cultural Foundation. It focuses on the politics of commoning, solidarity economy and common resources, gathering contributions from practitioners and collecting 20 inspirational cases from Europe and Turkey. I couldn’t launch it yet, actually due to the virus outbreak. Urban Commons in Turkey rose in response to the political crisis that started in the summer of 2013. People understood they could take action by joining different solidarity networks. In the Turkish case, the already existing local practices have increased in scale and visibility – there are several baskets in the streets where people can leave food for those who cannot afford it. As for more innovative ones, now there is an app to pay someone else’s bills, for example. These are indeed good signs, but unfortunately they don’t solve the many issues our society was already facing. Some of the current containment measures taken by the government don’t have constitutional basis – for example, only people over 60 are not allowed to leave the house, while most of the workforce still goes to work, since they can’t work from home. This increased the level of inequality in our society, giving rise to new waves of hatred towards elderly people who walk on the street for whatever reason, while the digital divide makes access to education harder for vulnerable groups. Not to mention the scary app launched by the Ministry of Health that traces Covid-19 positive people.

How are local authorities dealing with the crisis? In some cases they are building new alliances with associations in the field of commoning that can be used for the future.</b>

Martin Locret – I always try and be optimistic. I hope this can be a strong warning sign towards local authorities, but what we are doing right now is dealing with the emergency the best way we can. Meantime, we are trying to show that if we cooperate all the time we all could benefit from commons. Can we make this relationship evolve in the future? Does the state do what they can or much less? Dealing with urban spaces is always political, so we will keep on advocating for legal ways to occupy spaces, rent free. Simply because society will profit from it.

Duygu Toprak – Local governments’ response has been surprisingly in line with the commons’ thinking, but it is in conflict with the central government, so there is kind of a “competition” of solidarity campaigns between these two levels, basically asking citizens to donate, while the central government is being accused of hindering local initiatives, especially where local governments are led by opposition parties. This is even more discouraging, considering that citizens already pay taxes that are supposed to fund the containment measures. On the brighter side, I do see growing awareness from the municipal level.

Daniela Patti: Since commoning can have such a strong and positive impact on society, there has to be financial and bureaucratic support from the administration, but at the same time there needs to be a certain degree of autonomy.

Can hybrid financial models help urban commoning ensure viability and vision?

Public support is necessary, especially if you want to work with the most disadvantaged layers of society – and have a significant impact on it. Unfortunately, the neo-liberal agenda didn’t help – the non-profit sector is very often considered as just another business sector. It is very political to decide what you are going to do with public funds, so it is absolutely crucial to emphasize that the State continue to support what we do. At Community Land Trust, we think that land should be used for the common good and not as a speculative tool. By this we mean that planning should be done in another way. We tried to get together with other initiatives from the non-profit sector in order to create common spaces for us to use. We put together what we already had and decided to create a land cooperative. After all, I think this is the right moment. Should we keep living in this neoliberal world after the crisis, or should we rather begin a transition towards a socially, economically and politically just society? We will still advocate for state support, because if the state agrees we can really make a difference, but at the same time we will do our best to build the broadest possible movements that can support us both financially, in terms of political influence and social involvement.

We are now in the midst of the crisis, so it is difficult to think about the lessons learned, but what do you think we can learn from this situation?

Andrea Simone– We definitely learned that our community is vast and generous. Community can become more dispersed and fluid but still can thrive. I think that a state of emergency doesn’t provide the perfect conditions for big change, but it surely gives us the opportunity to become more resilient. We want mutualism to become an evermore stable reality. I think the boundary between associations and institutions are becoming thinner – some institutions that were never collaborative are now constantly looking for us. We expect consideration, respect, liberty and support from the city administration. Urban commoning cannot always be seen as a threat, as it is always depicted in the political discourse. We have changed more than five locations during the past three years, and we finally obtained a temporary location by the Municipality just a couple weeks ago, during the crisis. This must be valid also in the long run, not just for this emergency. I also think that the political measures that have been taken are not effective. Financial support is not distributed fairly, procedures are very long and complicated and most of all the most vulnerable groups are left out of this. Last but not least, at Nonna Roma we think that mutualism is the only way to make it through.

Ugo Mattei – We should come up with a common document. Everybody from the ruling élite is just talking about measures by governments and unions of states. This discourse is only about public money while many people are profiting from this crisis. We should require a different approach suggesting that because we are a community everybody should act reciprocally. We should refuse the paternalistic approach we are being force-fed by both the governments and the EU.

Natasha Dourida – Greece has some kind of an advantage in this. Greece was almost destroyed by the crisis of 2008, the people were left alone even by their own State, so solidarity mechanisms have already been put in place for more than a decade now. The reason why our society is relatively calm now is because we are taking a break, however absurd this may sound. We are still catching our breaths before the next blow, and we know that we won’t be alone because this time the issue is global. We have a different approach towards resistance, as we are tired of abiding by someone else’s rules even in suffering. So we can say we are developing our own creative ways of survival, while figuring out our own way out by ourselves. As a community, most of us are testing new ways – we are learning to grow our own food and we are becoming more energy-efficient, for example. A self-sustained economic model might find more willing ears in the forthcoming period, and initiatives like ours might actually thrive in the future.